“First of all, comedy does consist in the absence of something which is expected, but it can also consist in the presence of something where nothing is expected. Always, however, the situation must illustrate the absence of what ought to be, if it is to reveal comedy. The unexpected indication of the absence of perfection (the ought) constitutes the comic situation.”

—James K. Feibleman, “The Meaning of Comedy”

We live in an age in which we can make the case for politics as a form of theater. We seemingly also live in an age of comedy; or, said another way, comedy as genre, lens, and rhetorical mode functions as a primary means of delivering and processing information. News and analysis travel by memes, apps like TikTok, and programs like The Daily Show and Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. For at least a decade and a half—perhaps the inflection point that added the greatest momentum to this era is Saturday Night Live’s September 2008 introduction of Tina Fey as Alaskan Governor and vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin—comedy has been essential to helping us reconcile and understand our increasingly absurd and often unrecognizable world.

Selina Fillinger is both a student and master of perceiving the contemporary moment. Her play POTUS: Or, Behind Every Great Dumbass Are Seven Women Trying to Keep Him Alive skillfully combines political satire, parody-cum-backstage comedy, and farce to produce a scenario so outrageous that it will never happen. Yet, quite commonly, these days something once thought too ridiculous to occur happens. POTUS simultaneously epitomizes the zeitgeist and follows what has been the purpose of comedy dating back to the origins of western drama.

As a backstage comedy, POTUS takes place in a White House that amalgamates prior administrations and emerges from fevered amplification of possible future ones. The figures are nonpartisan composites drawn from both parties. We can recognize the unseen U.S. President in the play; we’ve seen traces of him in various leaders stretching back decades. He is a man who engages in extramarital affairs, excels at bullying, exhibits poor leadership, wields a hot temper, and appears woefully ill equipped for the job he holds. We have seen women in most, but not all, of the Executive Branch positions featured in the play, and this straightforward observation perhaps portends one of Fillinger’s percipient proffers.

POTUS begins in medias res, or without preamble, and at a rupture. In farce, the past is prologue. Circumstances fueling calamities and chaos that will unfold all stem from preceding events. Since the initiating problem has already occurred, characters find themselves in a game of catch-up as conditions spiral, new complications enter, and urgency ever increases. The play’s hapless head of state sets off concurrent crises, which the seven women closest to him must resolve. The women labor on behalf of the titular dumbass and endeavor to keep up appearances, which dramatizes the impulse to conserve the status quo. Early and often in POTUS, there is a sense that things aren’t working and something must change. But, how? Or, what? Or, who? While comedy sometimes provides escape from society’s problems, POTUS bids viewers to lean into our political dysfunction to contemplate pressing questions about our democracy and responsibilities as citizens.

The entanglement of politics and comedy trace back to the earliest forms of comedy for which we have historical records. The oldest form of stage comedy in western dramatic tradition are what’s known as Old Comedy, which dates to fifth century BC. All the works that shape our understanding of this initial phase in ancient Greek comedy come from a sole playwright, Aristophanes, whose dramatic output patently addressed political themes pertinent to Athenian institutions and democracy. In ancient Greece, theater performances took place during city festivals that were so important that attendance or participation was essential for standing as a good citizen. Broadly, ancient Greek tragedies centered on figures from traditional myths as a means of exploring an individual’s responsibility to self, family, and city-state. As tragedies routinely ended in unfavorable outcomes, lessons on how citizens ought to behave were often communicated by examples of how persons ought not behave; arguably, POTUS utilizes the same approach.

In contrast, Old Comedy concerned familiar and present political conditions, and public figures, officials, and prominent citizens were blatantly criticized and had their policies derided. Aristophanes acted as a conscience of the people and did not shy away from exposing corruption and political mismanagement and ridiculing the offenders. POTUS synthesizes tragedies’ interrogation of individual responsibility and representations of less than model behavior and Old Comedy’s analysis of current political zeitgeist.

Both comedy and politics are concerned with possibility. Aristotle once asserted that “politics is the art of the possible.” For Aristotle, possible refers to what is pragmatic. Yet, possible is capacious enough to hold anything that is conceivable, that which ought to be even if it hasn’t come to pass. Comedy shows us the folly in what is in order to arouse what could be, should be, and urgently must be. Comedy shows us the folly in what is in order to arouse what could be, should be, and urgently must be. Breaches in comedy provide ways of testing out different perspectives, alternative social formations, verboten romantic and sexual pairing, fantastic solutions to common problems, and the subversive and transformative nature of language. As experimental worldmaking, comedy journeys us from rupture to rapture. Like the preamble to the U.S. Constitution, POTUS’s project might be to encourage us to consider what is needed from each of us to move the nation in the direction of becoming “a more perfect union.” Or, perhaps, that’s too great a burden for a play, and its greatest ask is that we simply buckle up, lean in, and enjoy the ride; after all, this is a comedy.

Photo of Megan Hill, Kelly McAndrew, Natalya Lynette Rathnam, Yesenia Iglesias, Felicia Curry, and Sarah-Anne Martinez for POTUS by Tony Powell.

Tina Fey as Sarah Palin and Amy Poelher as Hillary Clinton in 2008 SNL Sketch. Dana Edelson, NBC.

Thalia, muse of comedy, gazing upon a comic mask (detail from Muses’ Sarcophagus).

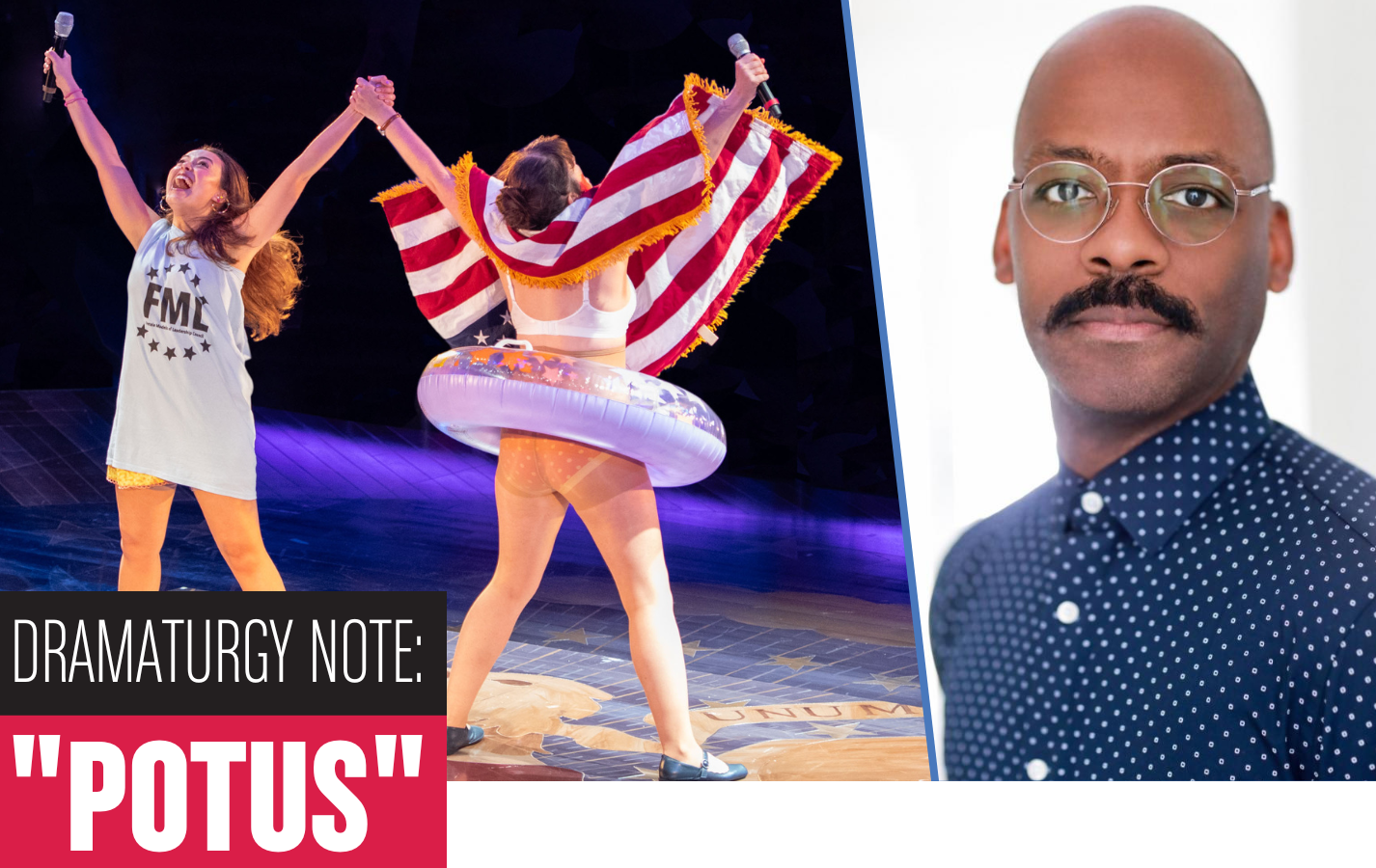

Photos of the cast of POTUS by Kian McKellar.