“Recognition or reknowing or unforgetting is, rather, a particular kind of perception; it is a sensation of seeing for the first time what one has seen many times before. One function of any art is to bring about that moment of unforgetting, when the familiar world suddenly seems strange and new or impossible.”

We have been here before. Soldier has been here before. We are here now—here in this theater, yes, but also in the reoccurrence of routinized violence against Black people.

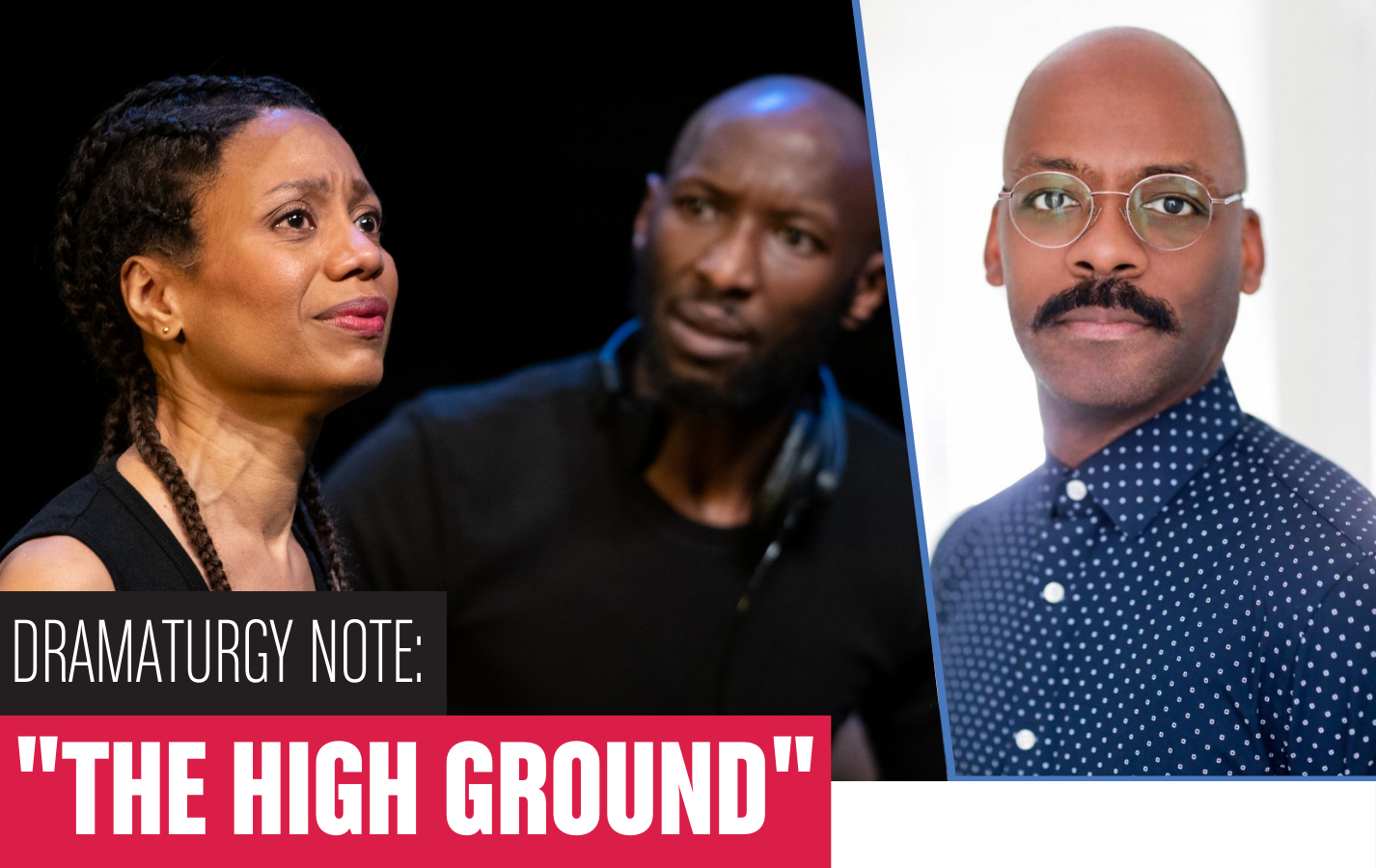

The High Ground, a play by Nathan Alan Davis, in conversation with the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, concerns events that are not firmly and solely in the past, events that won’t stay decidedly in any rearview mirror, events that resist redaction, and lamentably, events that seem to repeat and to return. The events of the play depict a type of strange loop, one in which violence against Black people is as common in this country as having a U.S. President named James, John, William, or George.

“And living in this order, black people are still doing the work in those innocent scenes. They're doing the work of dying; [...] That's really important work that we're called upon to do and still live under the specter of despotism.”

No one stands on any ground for the first time; rather, it may be the first time for a given individual but not for the ground. Someone, something has been here before. Perhaps, too, the spirit of what once occurred or what previously stood still lingers. Standpipe Hill, with views to the east towards Tulsa’s Greenwood District, provided a gathering post for Black residents to witness the razing of Black Wall Street. The High Ground is set atop Standpipe Hill in a present wherein figures and narratives inhabit and slip between time and modes of reality.

“An experience termed past may actually return if the influences have the same balances or proportions as before. Details may vary, but the essence does not change. The day would have the same feeling, the same character, as that day has been described as having before. The image of a memory exists in the present moment.”

We have been here before. On May 31-June 1, 1921, unabashed White violence razed the Black community of Tulsa. To this day, murky narratives describe the inciting events for the massacre. What we know—if indeed we can say that we know anything—is that on May 30, 1921, a Black teenager named Dick Rowland used the colored-only restroom on the top floor of the Drexel Building in downtown Tulsa. Sarah Page was the White seventeen year-old elevator operator in the building. Reports are that Sarah screamed, Dick ran, and a building clerk called the police and claimed that Rowland assaulted Page. For over a century, people have speculated about what happened. Might Dick have tripped and touched Sarah by accident? Was there any encounter at all? Did Sarah actually scream, and who heard it? Again, details are murky. The following day, the Tulsa Tribune printed incendiary articles titled “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator” and “To Lynch Negro Tonight.” A White mob gathered outside the courthouse, seeking to lynch Rowland. Their fury spread, and after eighteen hours of terror, as many as 300 people were killed and roughly 1,100 residences and dozens of businesses and churches were destroyed.

An extraordinary fact of these events is not that they happened, but that they were omitted from history texts in a pattern, which is the idea that the history of Black people in this country often jumps from Emancipation to Civil Rights. When we meet Soldier in the play, he is steadfast, determined, and vigilant in his determination to remember. Indeed, memory and recollection operate as resistance strategies for him.

“Memory and amnesia always exist side by side and remain part of a political struggle.”

Yet, Nathan’s play does not simply chronicle history. The play’s structure announces its rejection of the idea that we live apart from history. Nathan has crafted a world in which his meditations, research, history, and the present all collide in an intimate and theatrical inquiry around the phenomena of Black people in America living in such intimate proximity to death, and in being towards death, and existing in what has been termed “social death.” We need only recall that Tyre Nichols was brutally beaten by Memphis police officers on January 7, 2023 and died three days later on January 10, which also was our first day of rehearsal for The High Ground. We have been here before.

“The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized.”

Given the play’s topic, an interlocutor asked a question in the form of a statement, “So it’s another Black trauma play?”

There is a lot to unpack in this question, and I certainly do not wish to disparage any form of storytelling, but The High Ground does not focus on the terror and violence inflicted on Black people. Instead, the play acknowledges the antiblack violence that looms large and engages in worldmaking outside of those conditions.

Returning to the idea of a loop and being caught in a loop, the play proposes at least two practices as remedy. Recognition—seeing, really seeing one another, even if that person appears to be a homeless veteran—is one of the play’s suggestions. Another is a four-letter word (love), often uttered but seemingly harder to practice towards others.

Imagine how our world might change—even a little—if only we tried.

1Love