More than a century after the Tulsa race massacre killed hundreds and destroyed the prosperous Greenwood District, a Black man in army garb still stands his ground on present-day Tulsa’s Standpipe Hill. Traversing space and time, The High Ground is a lyrical story of the mysteries of love and loss, reminding us of what it takes to re-emerge from the devastation of a century, long after the embers have turned to ash.

Here are is some history you may find helpful to know before you see The High Ground. While none of this information is a prerequisite to understanding the play, we know there are some secret dramaturgs in our audience who will enjoy reading up in advance.

A TIMELINE OF THE GREENWOOD DISTRICT

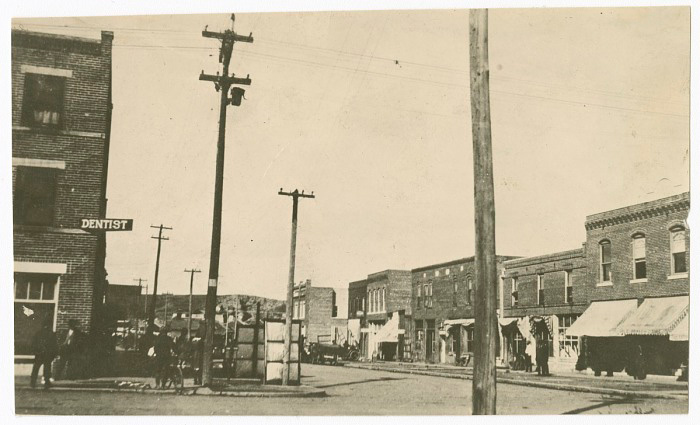

Greenwood District in Tulsa before 1921. (National Museum of African American History and Culture)

1900-1920

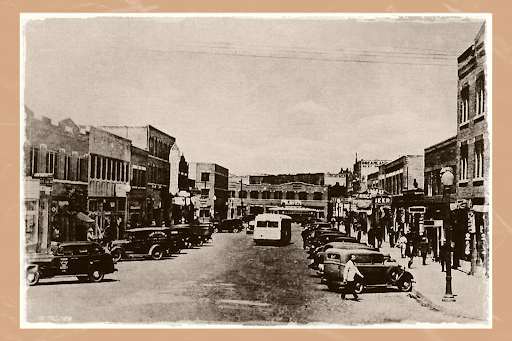

Built in the beginning of the 1900s, the Greenwood District was a thriving, wealthy Black community of around 10,000 in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It is commonly referred to as “The Black Wall Street” because of the financial successes of its many businesses. Churches, stores, medical offices, clubs, theaters, hotels, barbershops, salons, firms, among many other businesses, stood on the blocks of the district.

Only 60 years post-slavery and 40 years pre-integration, Black people were still viewed and treated as inferior in Tulsa, and many White Tulsans felt that the growing success of Greenwood was a threat.

Segregation was still legal in Oklahoma in the beginning of the 20th century. At the time, White Tulsans took the law into their own hands and created a group called the “Knights of Liberty” to punish anyone who dared challenge their norms. In the ten years before the massacre, 23 Black Oklahoma residents were lynched by White Oklahoman rioters. When the Knights of Liberty lynched a White resident whom they believed to be “radical,” the police chief of Tulsa called the Knights’ actions a benefit to the community. For the Greenwood occupants, this confirmed the partnership between the police department and those who were out to get them. On May 31, 1921, an angry mob of White Tulsans stormed the blossoming community and sparked what is known as the deadliest civic massacre in U.S. history.

A view of Greenwood Avenue looking north. (Greenwood Cultural Center / Getty Images)

May 30, 1921

Dick Rowland, a teenage Black shoe-shiner, entered an elevator on the morning of May 30. Teenager Sarah Page was working in the elevator as its operator. While there are many stories about the events that took place, it is commonly believed that Dick stepped on Sarah’s foot when walking inside. Sarah ran from the elevator. Dick also ran, knowing what could be perceived from White Tulsans seeing a White girl running from a Black boy, and what the consequences could be.

May 31, 1921

Two officers arrived at Rowland’s house to arrest him the next morning. By 3 p.m., a Tulsa newspaper featured an article about Rowland’s “attack” on Page. As the rumors spread through the city, hate and death threats began. Recognizing the trouble Rowland was in, Black Tulsans gathered at Greenwood’s beloved Dreamland Theatre to discuss the situation. They journeyed to the courthouse, offering to assist in protecting Rowland while he was being held by police. A White mob, already gathered at the courthouse, became upset by the Black Tulsans’ appearance. A member of the mob reached for a Black Tulsan’s gun, causing it to shoot. This shot is believed to be what started the massacre.

June 1, 1921

In the span of 18 hours, over 300 Black Tulsans were murdered, and the community was burned to the ground. Among the weapons used that day was the Gatling gun, an early machine gun that could shoot 200 rounds per minute. In addition to the ground warfare, Greenwood was also attacked from the air in small planes with some accounts of turpentine balls or dynamite being dropped from above. The residents of Greenwood worked to fight back, supported by their World War I veterans, but they were unsuccessful. The White mob that attacked Greenwood District worked with National Guard members, the sheriff, and his deputies to arrest 6,000 Black Tulsans and detain them under armed guard in places like the Convention Hall, the Tulsa Fairgrounds, and McNulty Park.

Destroyed Homes in Greenwood. (National Museum of African American History and Culture)

February 28, 2001

The city officially acknowledged the massacre when they published “A Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921” on February 28, 2001.

REMEMBERING THE MASSACRE

Our knowledge of the events of the Tulsa Race Massacre can be credited to the survivors who kept records of their experiences to ensure that history was not erased. Through the preservation of their recollections, historians were able to piece together the facts of the massacre. Two women in particular should be recognized for their tremendous contributions to the information we have today: Mary Parrish and Eddie Faye Gates.

Mary Parrish (1892-1972) was a teacher, writer, and journalist. Originally born in Mississippi, Parrish was attracted by the Black unity of Greenwood and eventually moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1919 with her daughter. There, she founded her school for typewriting and stenography, the Mary Jones Parrish School of Natural Education. There, they witnessed the Tulsa Race Massacre. After the massacre, Parrish began to interview survivors, gathering stories and research. In 1923, she published a book about the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Eddie Faye Gates (1934-2021) In the 1990s, Oklahoma sanctioned a committee to research and analyze the Tulsa Race Massacre. Eddie Faye Gates spent summers in Tulsa as a teenager and her passion for history led her to join the Tulsa Race Riot Commission. Gates was chosen to lead locating all the living massacre survivors, some of whom were as young as five on the day of the massacre. She and the commission found 118 survivors. Like Parrish, she interviewed survivors, recorded their accounts, and fought for policies that would provide support and reparations for the victims.

THE GREENWOOD DISTRICT TODAY

By the 1950s, Greenwood had rebuilt its community, dedicating serious efforts to restoring the success of the former Black Wall Street. However today, all that is reminiscent of the pre-massacre district is a block of Black businesses and the Vernon Chapel AME Church, making space for new developments like restaurants and galleries. Some feel that these new renovations contribute to the gentrification of Greenwood and the erasure of what was.

For decades, the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre was little known or discussed in American popular consciousness. But many have worked to document this tragic chapter. More information on Greenwood is available through the Women of Black Wall Street Project, a resource for the team behind The High Ground. DeNeen Brown of The Washington Post has also covered the massacre and its aftermath. Today, the massacre is becoming a more widely known part of American history, largely due to its inclusion in television shows like Watchmen and Lovecraft Country. The High Ground continues this poignant exploration of a once-thriving community and its enduring legacy.

Nehassaiu deGannes (Victoria/Vicky/Vee/The Woman in Black) and Phillip James Brannon (Soldier) in The High Ground. Photo by Margot Schulman.