“To sow the wind is to reap the whirlwind.”

— Anna Julia Cooper, “The Ethics of the Negro Question”

“Having now seen how quickly the truth can become a casualty amid controversy, I’d urge a broader caution: At tense moments, every one of us must be more skeptical than ever of the loudest and most extreme voices in our culture, however well organized or well connected they might be. Too often they are pursuing self-serving agendas that should be met with more questions and less credulity.”

— Claudine Gay, “What Just Happened at Harvard Is Bigger Than Me”

In 1870, Congress established the Preparatory High School for Negro Youth in DC. In 1891, the school was relocated and became popularly known as the M Street High School. The school gained a reputation for producing women and men of excellence who went on to attend elite colleges and universities and rose to prominence in many professional fields including business, dentistry, education, law, medicine, the military, music, and teaching. Illustrious educator, scholar, and activist, Anna Julia Cooper became principal at M Street on January 2, 1902. Cooper’s book A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South (1982) is considered one of the first published articulations of Black feminism and earned her the honorific “the mother of Black feminism.”

Inspired by real events, Tempestuous Elements dramatizes events that occurred during Cooper’s tenure as principal. The play is best viewed with awareness that events represented therein occurred after Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) upheld racial segregation in public accommodations, including schools and before Brown v. Board of Education (1954) would rule segregations in public schools unconstitutional. The Plessy ruling illustrates a post-Emancipation struggle against limits of citizenship for Black Americans and a larger discourse around the possibilities of social equality between Blacks and whites. As a woman, Cooper was additionally subject to gender-based biases, and she wrote and spoke about her specific positionality as a Black woman subjected to both racism and misogyny. Over one hundred years before Black feminist writer Moya Bailey coined the term “misogynoir” to describe the intersection of these two oppressions, Cooper’s work was steeped in the very idea.

While, as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. suggests, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” it can sometimes feel like we are standing still or at least, in some ways, pushing a heavy stone up a steep hill. Cooper was not the first, and a cursory glance at recent events confirms that she will not be the last, Black woman to be attacked and vilified by those wishing to curtail progress. In 2021, Nikole Hannah-Jones was refused tenure at the University of North Carolina in the wake of concerted action against her appointment. While UNC eventually flip-flopped on their position and offered Hannah-Jones a tenured post, she refused it, and instead joined the faculty of Howard University.

When we gathered on January 17th for the first rehearsal, only two weeks had passed since Claudine Gay resigned her post as president of Harvard University. In a New York Times guest essay, Gay reflects, “It is not lost on me that I make an ideal canvas for projecting every anxiety about the generational and demographic changes unfolding on American campuses: a Black woman selected to lead a storied institution. Someone who views diversity as a source of institutional strength and dynamism.” According to Nancy Kober, a Consultant for the Center on Education Policy, “The Founding Fathers maintained that the success of the fragile American democracy would depend on the competency of its citizens.”

If, as the Founding Fathers suggested, the health of our democracy depends upon the health of our educational institutions, how is our democracy fairing when what happened to Anna Julia Cooper keeps on happening and happening?

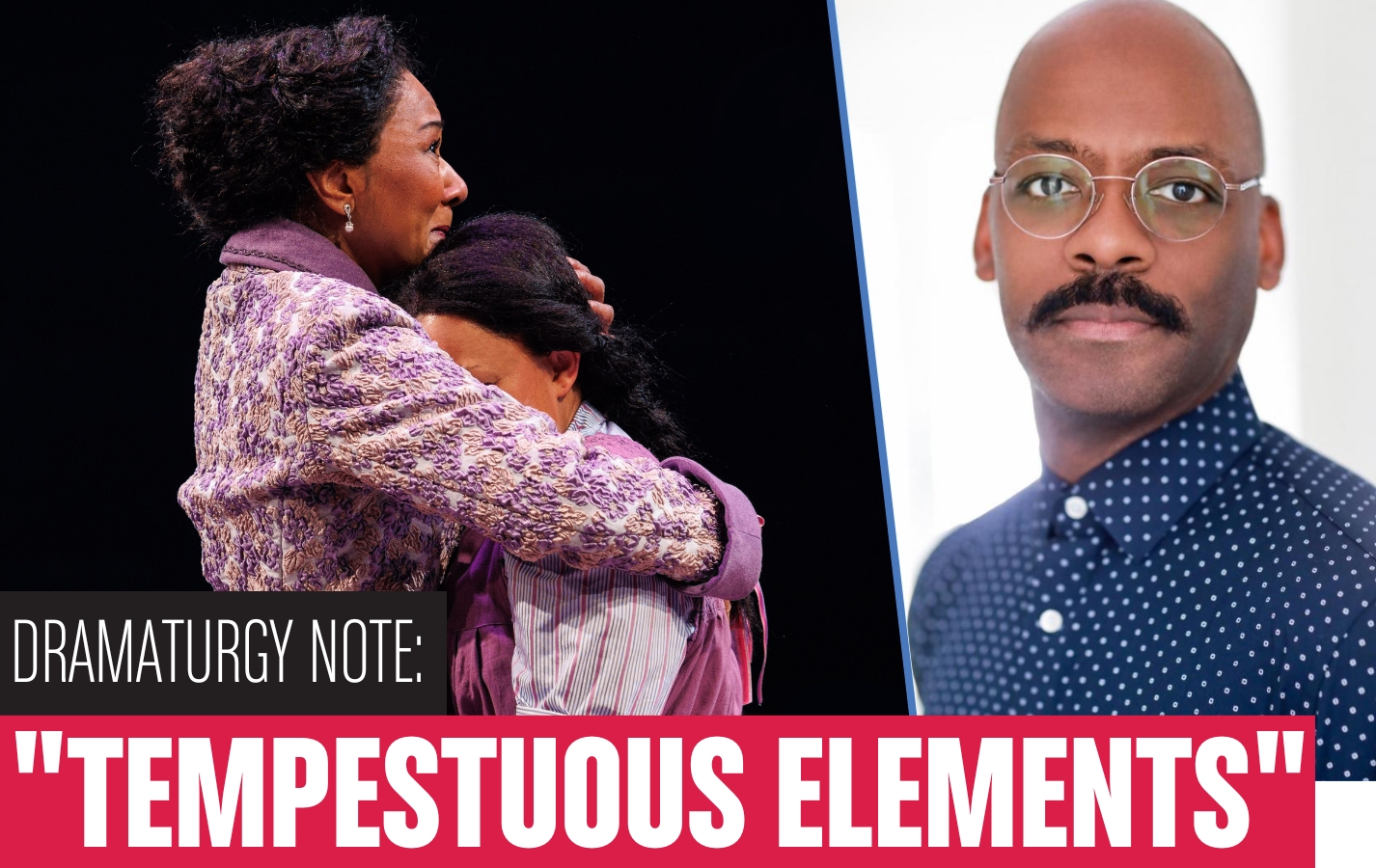

Photo of Gina Daniels and Brittney Dubose in Tempestuous Elements by Kian McKellar