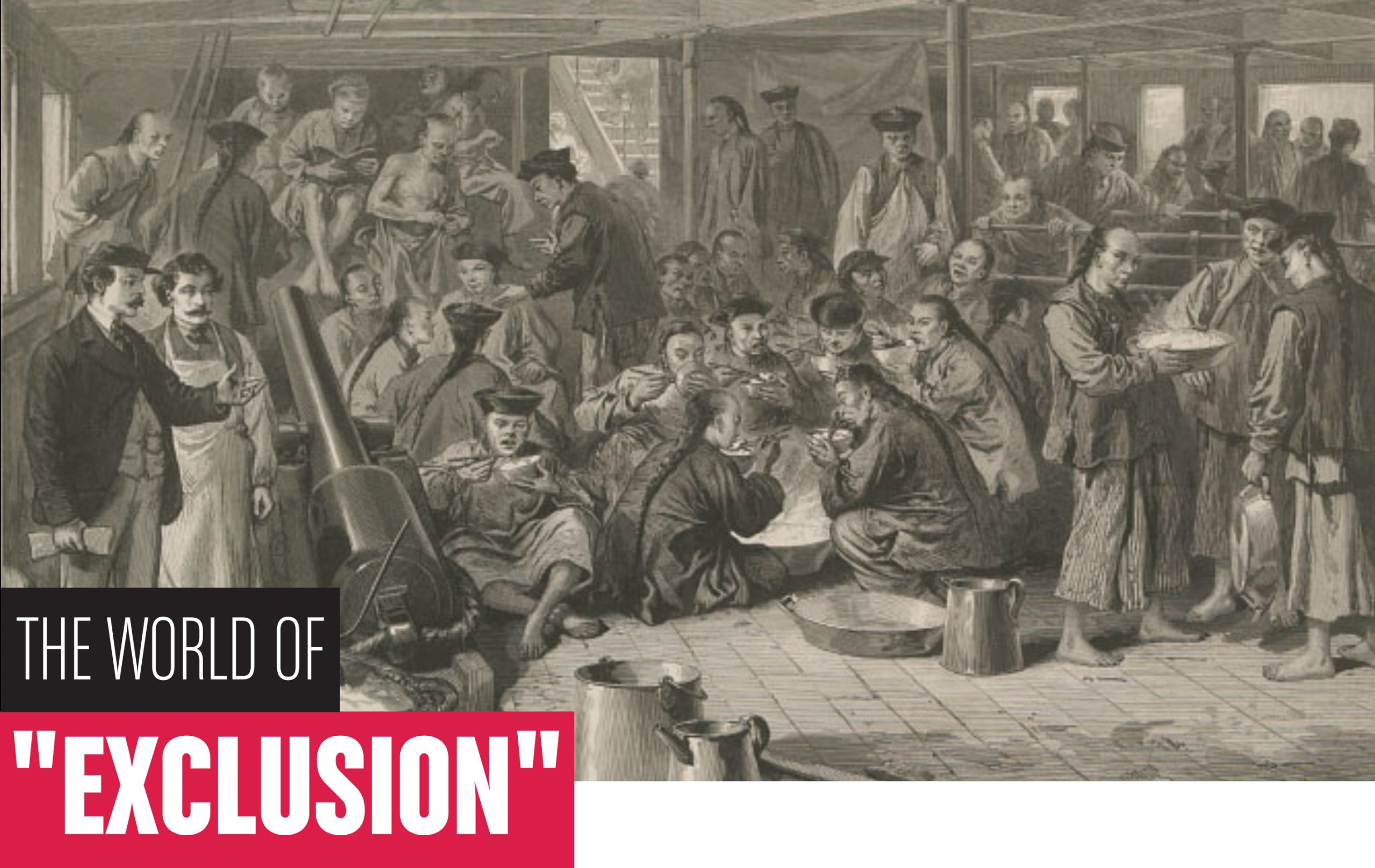

“On Board the Pacific Mail Steamship ‘Alaska'” (artist unknown), Harper’s Weekly, 20 May 1876, pp. 408-409; University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

As you prepare to see Exclusion, it is helpful to know the historical context that frames its narrative. This play explores the often-neglected narratives of Chinese-American history. To fully appreciate the significance of Exclusion and the fervor driving its main character, Katie Ng, familiarize yourself with the background information that forms its foundation.

Chinese-American History

PRE-IMMIGRATION

In the mid-19th century, China was in severe debt and political turmoil as the result of floods, droughts, fighting the British in the Opium Wars, and the Taiping Rebellion. By 1852, an extremely unsuccessful year for crops in China, Chinese workers left the country to support their families. Drawn by the California Gold Rush, 20,000 Chinese people, mostly men, migrated to San Francisco, California to find work.

IMMIGRATION TO U.S.

After the Civil War and the abolishment of slavery, there were gaps in the workforce. Chinese immigrants were able to fill the demand for low-wage labor. They entered various industries including laundry, agricultural, domestic, factory, and eventually, railroad work. Chinese workers were essential to the building of the Transcontinental Railroad.

Chinese workers were also crucial in the success of the Gold Rush, but, as a result, tensions rose almost immediately between the American miners and the Chinese immigrants. The new arrivals faced xenophobia, racism, and mistreatment from the Californians and their government. Anti-Chinese sentiment and hate crimes increased with the goal of getting Chinese people out of the country.

In 1852, the Californian government passed the Foreign Miners License Tax in an effort to deter Chinese immigrants from working. It charged the new immigrant miners $3 a month, the equivalent of about $117 in today’s dollars.

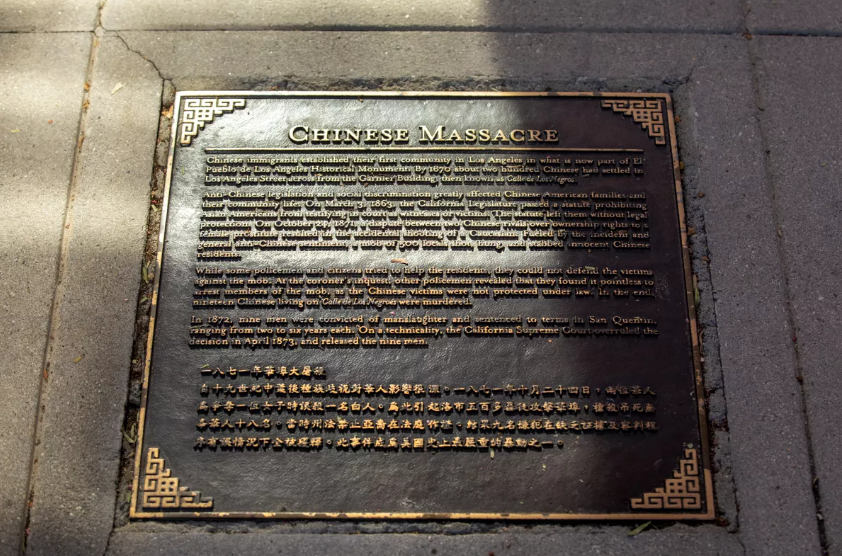

A plaque on the sidewalk near the Chinese American Museum commemorates the Chinese Massacre of 1871. (Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

THE CHINESE MASSACRE OF 1871

In 1869, the Los Angeles News and the Los Angeles Star began to release anti-Chinese publications, expressing their desire for Chinese people to stay out of the U.S. and condemning the entire race.

In 1871, a shootout between two Chinese rival groups occurred in Chinatown in Los Angeles because of a dispute. Two officers responded to the scene. An officer and well-known resident named Robert Thompson were both shot and killed during the shootout.

Hearing the news of Thompson’s death, around 500 non-Chinese residents formed a mob for vengeance. They prepared a section of gallows, forcibly removed the Chinese residents involved in the shooting from their hiding spot at the Coronel Building, and publicly hanged each one of them.

The next day, the bodies of the Chinese men and boys were laid out on the jail grounds. Historical accounts differ on the number of people that were murdered in the massacre, estimates alternating between 18 and 19. According to the U.S. Census, out of the total 5,728 people living in L.A. only 172, or 3%, were Chinese. This means 10% of the Chinese population in L.A. was murdered during the massacre. According to the Los Angeles Public Library, out of all the men and boys killed that day, only one of them was actually involved in the original shootout.

Of the 25 people charged, only ten men responsible for the hanging were taken to court. Of those ten men, only eight were found guilty of manslaughter. These charges were eventually overturned, and there was never another trial. Because of the 1854 California Supreme Court Case, People v. Hall, Chinese immigrants did not have the right to testify in court against white European Americans. The resulting legal action taken presented clear prejudice by the justice system.

L.A. swiftly moved on from the massacre, failing to even mention it in the local newspaper’s yearly wrap-up of important events. Even today, many in the U.S. are unaware that the Chinese Massacre of 1871 occurred.

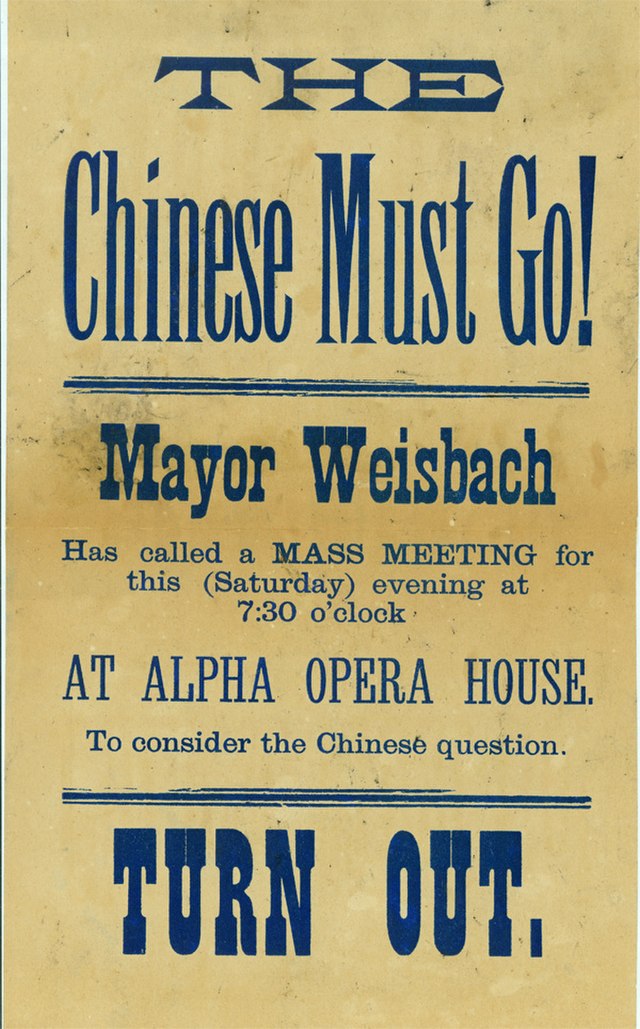

The Chinese Must Go – Mayor Weisbach at Alpha Opera House poster, Tacoma, Washington Territory 1885

THE CHINESE EXCLUSION ACT OF 1882

With the influx of Chinese immigrant workers, Americans began to blame them for lowering wages and causing economic troubles on the West Coast. As a result, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 into law, banning Chinese workers from immigrating to the United States for ten years. It was the first U.S. law to put a restriction on the immigration of one group. Chinese residents who were not laborers and wanted to enter the U.S., such as a diplomatic agent, had to receive official certification from the Chinese government proving their status. Those who were already living in the U.S. would need new certifications to reenter the country if they left. Those living in the U.S. who were not citizens were denied the right to become citizens, facing the possibility of deportation.

Once the ban reached its 10-year mark in 1892, Congress passed the Geary Act: a U.S. law that extended the Chinese Exclusion Act for 10 more years and added new restrictions. One was the requirement for Chinese immigrants to obtain a Certificate of Residence to prove that they were legal immigrants, or else they faced the possibility of deportation. Congress continued to update their quotas (official restrictions on the number/percentage of people from a certain group being allowed to do something) as well as their requirements for immigration, expanding their lists of countries to include all of Asia. In 1902, immigration from China was ruled illegal.

It was not until 1943 that Congress revoked all the exclusion acts, and Chinese immigrants were given the right to become citizens. This was due to China’s support of the Allied Nations during World War II. However, there was still a yearly cap of 105 Chinese immigrants to the U.S.

AAPI TREATMENT TODAY

Discrimination toward people of Asian descent runs deep in America’s history, and as a result, the AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) community has experienced harassment, discrimination, violence, and hate in the United States. After the COVID-19 outbreak, there was an increase in AAPI hate. Fueled by xenophobia, racism, and ignorance, some blamed the AAPI communities for the global pandemic. Since then, there has been an increase in AAPI hate crimes. According to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, anti-Asian hate crimes increased by 124% in the year 2020, and by 339% in 2021.

In response to this increase, the coalition Stop AAPI Hate was formed on March 19, 2020. The coalition is made up of AAPI Equity Alliance, Chinese for Affirmative Action, and the Asian American Studies Department of San Francisco State University. The coalition “tracks and responds to incidents of hate, violence, harassment, discrimination, shunning, and child bullying against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States.”

Conclusion

Having familiarized yourself with the historical context that frames the narrative of Exclusion, you are now prepared for its powerful impact. By exploring the often-neglected narratives of Chinese-American history, this play sheds light on important aspects of our collective past. Come experience this “thought-provoking and witty world premiere” (BroadwayWorld) for yourself. Tickets are now available. Exclusion runs through June 25.