Reprinted with permission from Berkeley Repertory Theatre.

Once the calling card of dissatisfied youth, rock and roll has long since left its defiant countercultural attitude behind and nestled itself snugly into mainstream musical history. Though the edges of rock music’s past have rounded over time, its raucous spirit can still be felt, particularly in arenas where no real lineage of disorderly conduct exists. As New York Times pop music critic Jon Pareles notes, “Broadway may be the final place in America, if not the known universe, where rock still registers as rebellious.”

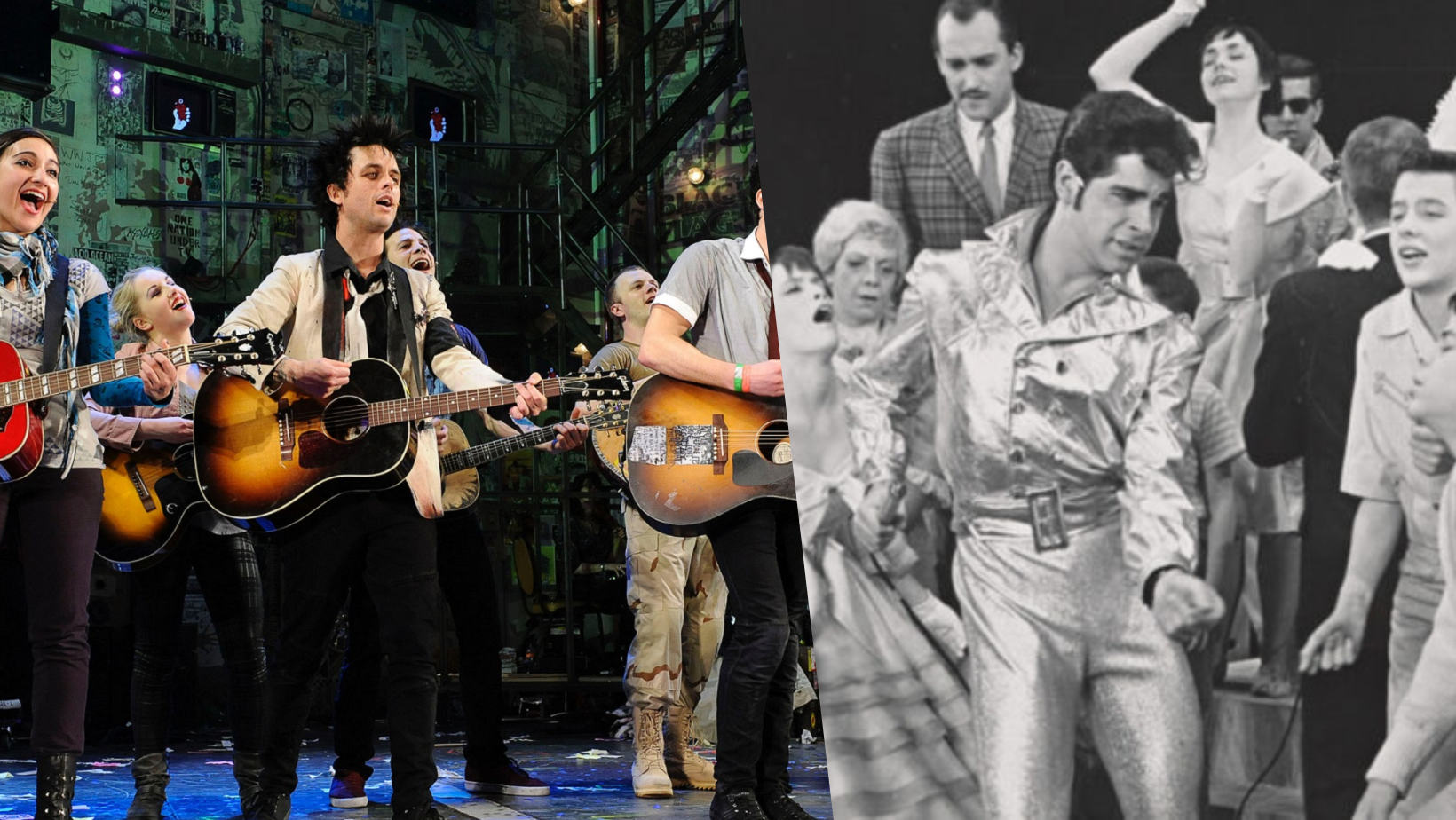

Believe it or not, Bye Bye Birdie is largely considered to be the first rock musical. Written in 1959, this send-up of rabid Elvis fandom featured two songs that reached beyond the boundaries of the showtune toward a more contemporary sound. While the rest of the score lived firmly in familiar territory, “Honestly Sincere” and “One Last Kiss” helped to usher in an evolution that both embraced legacy and simultaneously invited something new. It’s fitting that defining lines were blurry right from rock and roll’s earliest appearances on the musical stage.

Popular music and Broadway showtunes used to be synonymous. A song from a musical might be covered by the day’s most popular artists, and a hugely popular song often began its life as part of a show. The canon of music in the United States from the 1920s through the 1960s known as the “Great American Songbook” contains a vast quantity of showtunes. Many songs we might think of as standards originally came from Broadway: “Summertime” (Porgy and Bess), “Send in the Clowns” (A Little Night Music), “You’ll Never Walk Alone” (Carousel), “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered” (Pal Joey), “Big Spender” (Sweet Charity), “Some Enchanted Evening” (South Pacific), and the list goes on.

Rock and roll began to eclipse American standards on the music charts, paving the way for the rock musical to emerge in earnest. 1967’s Hair marked the first true rock and roll score, and the first time a Broadway production featured instrumentation arranged primarily for guitar rather than piano. The 70s saw the genre flourish with shows like Jesus Christ Superstar, The Wiz, and Grease. Public appetite shifted a bit in the 80s towards a more traditional musicality, but rock roared back in the 90s led by Rent and Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and remains a popular milieu for composers looking to write for the stage.

Sometimes an artist’s existing catalog serves as the heartbeat of the show, and a narrative (some looser than others) is crafted around it. Referred to as a “jukebox musical,” well-known examples include Jersey Boys and Ain’t Too Proud—The Life and Times of the Temptations. Artists from Carole King to Fela Kuti have had their body of work used as source material for Broadway. A concept album, where a narrative arc encompasses a collection of songs, such as The Who’s Tommy, might also prove fertile fodder for creating a theatrical experience. In other instances, the lines aren’t as clean. Green Day’s American Idiot threads characters and references throughout the album, but does so without a linear progression of storyline. The stage version added minimal text, and largely found its story through choreography, costume, and other theatrical techniques. Passing Strange combined songs from Stew and The Negro Problem’s existing catalog with new songs and added text to find its form.

Musicals have broadened their reach and scope to encompass a wide range of songwriting. The last twenty years have seen girl pop, R&B, hair metal, punk rock, and more make appearances in theatres across the country. This season at Berkeley Rep alone, you can see musicals incorporating an entirely a cappella score, 60s Cambodian rock hits, Kenyan Jazz and Afrobeat, and of course, the indie-folk-Americana stylings of The Avett Brothers.

The band, made up of siblings Scott and Seth Avett, along with bass player Bob Crawford and cellist Joe Kwon, released their first official album in 2001 and their popularity has snowballed over the ensuing years. Their introspective, intimate lyrics paired with a fierce commitment to craft and structure have gained them a loyal and ever-growing audience. They exude a guileless honesty that can win anyone over. Known for their dynamic live performances, an Avett Brothers show offers the concert equivalent of an athlete leaving it all on the field.

Their songs often unfold like little stories unto themselves: three to four minutes of perfectly-shaped sentiment set to inspired melodies that send the lyrics soaring. The Avetts’ 2004 release Mignonette also had a loose über-story, earning it status as a concept album. Mignonette is inspired by the tale of an 1884 sea voyage, a shipwreck, and the struggle of four men to survive — subject matter rife with dramatic potential.

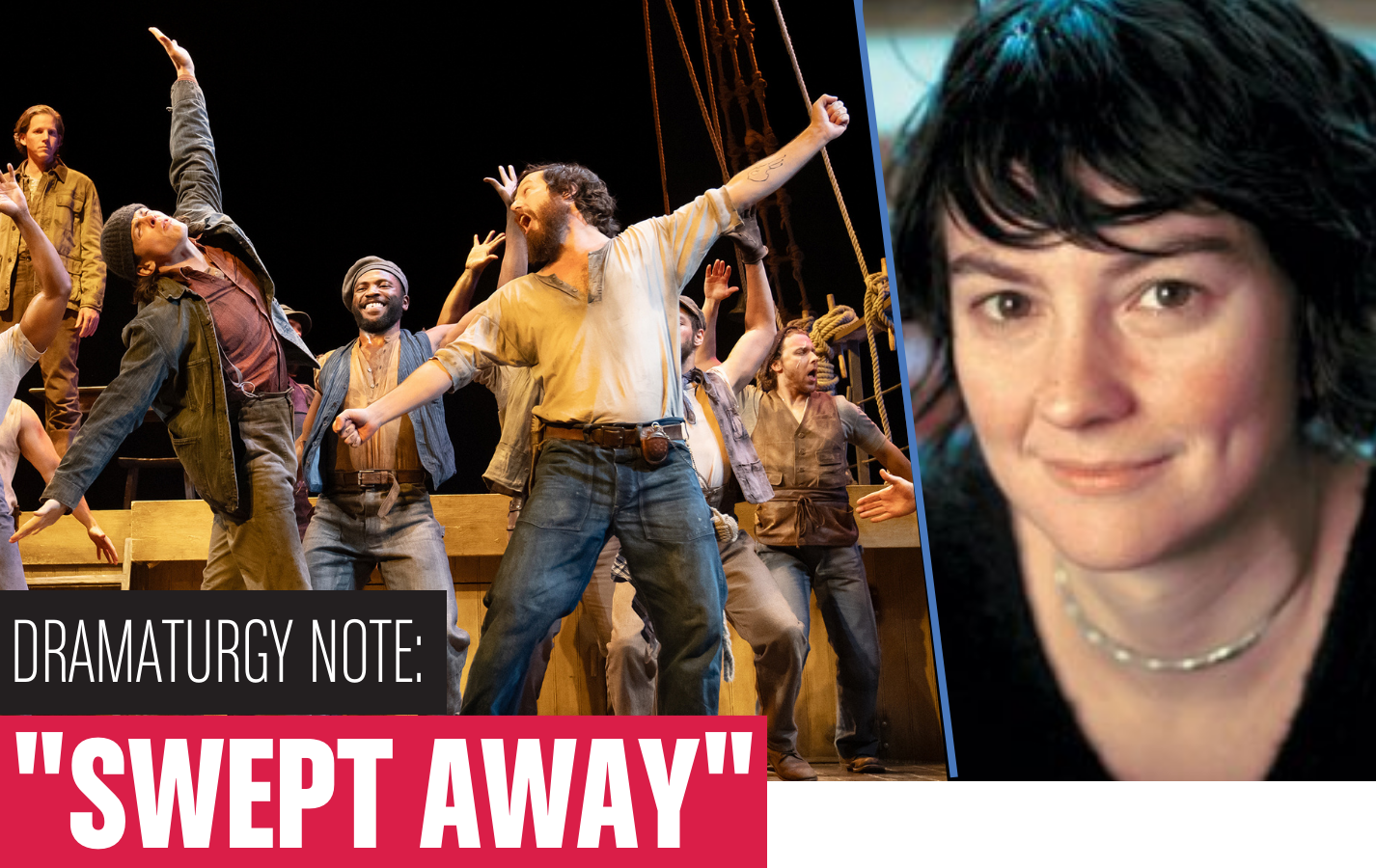

Swept Away takes that potential and transforms it into an epic ninety minutes of swagger and spirit. The show depicts high drama on the high seas, defying convention through its sound and source material. The production transcends bygone definitions of what constitutes a musical and helps to carry this time-honored stage tradition into the present and beyond.

Orville Mendoza (Ensemble), Taurean Everett (Ensemble), Stark Sands (Big Brother), Adrian Blake Enscoe (Little Brother), Jamari Johnson Williams (Ensemble), John Gallagher, Jr. (Mate), Michael J. Mainwaring (Ensemble), John Sygar (Ensemble), and Matt DeAngelis (Ensemble) in Arena Stage’s East Coast premiere of Swept Away. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

Photo of Billie Joe Armstrong on the final night of American Idiot‘s Broadway run courtesy of Getty.

Photo of Dick Gautier in the 1960 Broadway musical Bye Bye Birdie courtesy of Photofest.

Photo of Kate Baldwin in Arena Stage’s South Pacific (2002/03 Season) by Scott Suchman.

Photo of the cast of Arena Stage’s Carousel (2016/17 Season) by Maria Baranova.

Photo of The Avett Brothers by Crackerfarm.